The growing number of public schools that require students to pay a fee to participate in after school activities, such as sports or music, is exacerbating the economic class disparities in America’s schools, and diminishing opportunities for students from families of limited financial means.

“Play to play must end,” said social scientist Robert Putnam, a professor of public policy at Harvard University, and author of the best-selling book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, appearing in Hartford in a special event sponsored by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.

Putnam, who rose to cultural prominence in 2000 with his book “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of the American Community,” mixed riveting stories of the vastly different life experiences of the nation’s children, depending upon the financial wherewithal of their parents, and the dangers to every aspect of society - rich and poor - of permitting the growing disparities to continue unchecked.

According to his data, 86 percent of students from the highest-income families participate in extracurricular activities — slightly higher than during the 1970s — but participation among the lowest-income families is down about 15 percentage points, to 65 percent.

“No one talked (50 years ago) about soft skills, but voters and school administrators understood that football, chorus, and the debate club taught valuable lessons that should be open to all kids, regardless of their family background,” Putnam writes in the book.

Pay to play policies have been evident in Connecticut, as elsewhere across the country, for some time, as reflected in data compiled by the state Office of Legislative Research (OLR) in 2012. The OLR report included information from 116 school districts. Of these, “44 charged a participation fee for high school athletics. The fees range from $25 per sport to $1,450 for ice hockey. Twenty nine school districts include a maximum amount that a student, family, or both can be charged during a single school year. Schools without a cap are generally those that charge the lowest fees.”

Following that report, legislation that would have prohibited local and regional boards of education from charging any student activity fees to students who are unable to pay such fees was considered in 2013 but not approved by the state legislature.

Last month, education officials in Norwalk proposed requiring student athletes to pay $100 each to participate athletic programs. Published reports indicated that students who participate in high school musicals in the city pay about $200 as a participation fee.

Putnam noted that although many school districts that charge such fees provide for waivers for financial need, those tend not to be used because students would rather drop a sport than be stigmatized as poor and needy. And he emphasized that dropping out of participation in after school activities worsens development and lessens chances to break away from a life of diminished opportunities. The absence of such extra-curricular participation adversely impacts both future circumstances and physiological developmental, Putnam said.

The OLR data indicated that in Trumbull, for example, a family could pay as much as $750 (or $900 including hockey) for students’ participation in sports; in South Windsor the payment was capped at $500 per family, or $800 including hockey. In Region 10, which includes the towns of Burlington and Harwinton, there was a maximum of $450 per family for participation in sports.

The Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference Handbook for 2016-17 includes reference to the organization’s “strong opposition to the local board of education policies which establish a fee system for students who wish to participate in co-curricular or extra-curricular activities, athletic and/or non-athletic.”

The Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference Handbook for 2016-17 includes reference to the organization’s “strong opposition to the local board of education policies which establish a fee system for students who wish to participate in co-curricular or extra-curricular activities, athletic and/or non-athletic.”

Among the organizational policy positions included in the handbook, the Administrators of Health and Physical Education “feel a direct assessment on the individual families of athletes is contrary to the educational philosophy so deeply rooted in our nation, and is wrong because it places an undue tax on selected members of the community.”

“Athletics as an extra-curricular activity is unique in that it provides a possible predictor of student success in later life; and affords adolescent boys and girls an opportunity to establish a physical and social identity along with the intellectual identity they develop while in the classroom,” the Administrators of Health and Physical Education policy statement says.

The handbook section on “pay to play” continues, indicating that “In support of that notion is a pair of studies conducted by the American Testing Service and College Entrance Examining Board. The former completed a study comparing four factors thought to be possible predictors of student success: achievement in extracurricular activities, high grades in high school, and high grades in college as well as high scores on the SAT. It was found that the only factor which could be validly used to predict success in later life was achievement in extra-curricular activities.”

Adds the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents: “Free public education includes the student’s right to participate in activities offered by a school district. The student should not be denied participation because of lack of funds or the refusal to pay a fee.”

Putnam, speaking at the Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts to a nearly filled Belding Theater audience, recalled attending Yale University in Connecticut, and speaking in Hartford 16 years ago, when Bowling Alone was published. He stressed that there are fewer mixed-income neighborhoods than there were 50 years ago, and as a result children are less likely to go to school with people of a different social class.

The top third of US society – whether defined by education or income – are investing more in family life, community networks and civic activities than their parents, while the bottom third are in retreat, as families fracture and both adults and children disengage from mainstream society, he pointed out. That is evident in a range of statistics, he said, proceeding to share a series of graphs and charts that underscored his thesis.

Putnam identified causes of the widening opportunity gap for the current generation of young people as the collapse of the working class family, a substantial increase in single-parent homes among the poor, economic insecurity among growing cadre of working class people, and a cultural change of people no longer looking out for other people’s kids in a way that happened in the past. The definition of “our kids,” he said, has narrowed for a community’s children, to the biological children of individual families.

This gap amounts, Putnam emphasizes, is a “crisis” for the American dream of equal opportunity. Advantages pile up for the kids born to the right parents, all but guaranteeing their own success in life – in stark contrast to the fates of those struggling at the bottom.

Among the statistics of concern raised by Putnam: affluent children with low high-school test scores are as likely to get a college degree (30%) as high-scoring kids from poor families (29%). And he called for a focus less on the costs of community college and more on helping students unfamiliar with the bureaucracy and processes of college work their way through it. “We need navigators to help these students navigate the process,” he said, making a comparison to health care, where newly diagnosed cancer patients, unfamiliar with the world they have just entered, increasingly have “health care navigators” assigned to them as guides to deal with the uncertainty they face.

Despite the preponderance of evidence showing stark disparities, Putnam says he is optimistic that the trends can be reversed. “American did it once before, after the turn of the last century,” he explains, and can do so again. He suggests that the remedy will more likely be driven from the grassroots, in individual communities, than from policies adopted by the federal government.

Dunkin’ Donuts Park is the first brand new venue to open in the Eastern League since Northeast Delta Dental Stadium—home of the New Hampshire Fisher Cats—opened its doors in 2005, and it is seen as the biggest change to the league’s facility landscape since the extensive multi-phase renovation to the Harrisburg Senators’ FNB Field was completed prior to the 2010 season.

Dunkin’ Donuts Park is the first brand new venue to open in the Eastern League since Northeast Delta Dental Stadium—home of the New Hampshire Fisher Cats—opened its doors in 2005, and it is seen as the biggest change to the league’s facility landscape since the extensive multi-phase renovation to the Harrisburg Senators’ FNB Field was completed prior to the 2010 season.

Organization vanity plates include Amistad, Benevolent & Protective Order of the Elks, IUOE Local 478, Grand Lodge of Connecticut, Knights of Columbus, Olympic Spirit, P.T. Barnum Foundation Inc., Preserving Our Past CT Trust for Historic Preservation, Red Sox Foundation, Lions Eye Research Foundation, Special Olympics, Federated Garden Clubs, Fidelco Guide Dog Foundation, Keep Kids Safe, New England Air Museum and the U.S.S. Connecticut Commissioning Committee.

Organization vanity plates include Amistad, Benevolent & Protective Order of the Elks, IUOE Local 478, Grand Lodge of Connecticut, Knights of Columbus, Olympic Spirit, P.T. Barnum Foundation Inc., Preserving Our Past CT Trust for Historic Preservation, Red Sox Foundation, Lions Eye Research Foundation, Special Olympics, Federated Garden Clubs, Fidelco Guide Dog Foundation, Keep Kids Safe, New England Air Museum and the U.S.S. Connecticut Commissioning Committee.

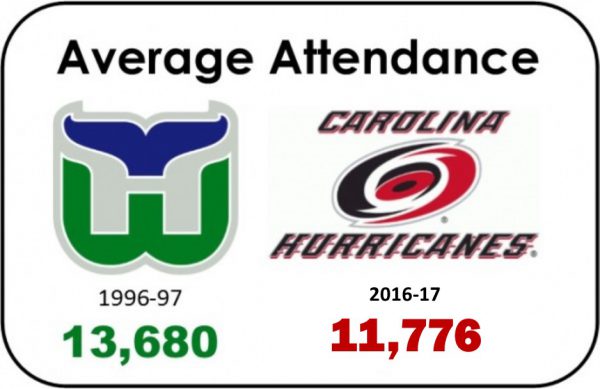

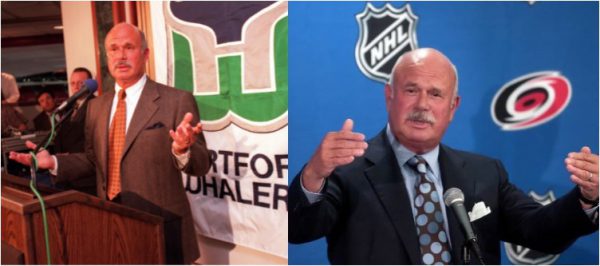

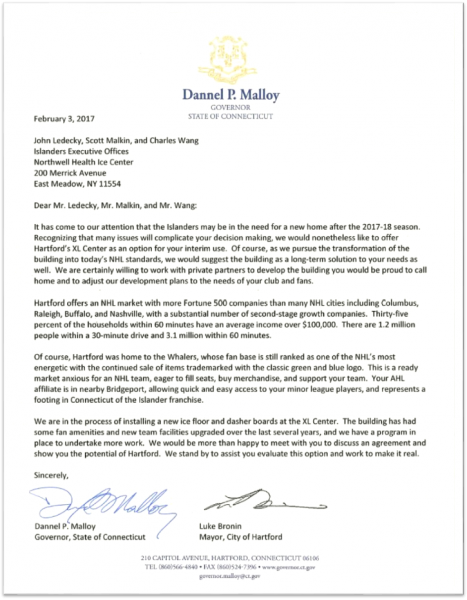

ades of highs and lows as the Carolina Hurricanes – two Stanley Cup appearances, and one win of the Cup in the early years, and the worst attendance in the National Hockey League, or near the bottom, more recently. In Hartford, the Whalers

ades of highs and lows as the Carolina Hurricanes – two Stanley Cup appearances, and one win of the Cup in the early years, and the worst attendance in the National Hockey League, or near the bottom, more recently. In Hartford, the Whalers

Lowest

Lowest

“The cyclocross national championships are the pinnacle of cyclocross racing in the United States each year,” said Micah Rice, Vice-President of National Events, USA Cycling. Cyclocross is a very specific type of bike racing, as described by Cyclocross Magazine. For the most part, the course is off-road but there are sometimes portions of pavement included in the course. Riders can expect to encounter grass, dirt, mud, gravel, sand, and a whole slew of other assortments and combinations. The races are based on a set time (measured by numbers of laps), not distance. Depending on your category, a race can be as quick as 30 minutes (for beginners), or as long as 60 minutes (for pros).

“The cyclocross national championships are the pinnacle of cyclocross racing in the United States each year,” said Micah Rice, Vice-President of National Events, USA Cycling. Cyclocross is a very specific type of bike racing, as described by Cyclocross Magazine. For the most part, the course is off-road but there are sometimes portions of pavement included in the course. Riders can expect to encounter grass, dirt, mud, gravel, sand, and a whole slew of other assortments and combinations. The races are based on a set time (measured by numbers of laps), not distance. Depending on your category, a race can be as quick as 30 minutes (for beginners), or as long as 60 minutes (for pros).

“The New England Region is looking forward to the expansion of two weekends for our Winterfest tournament,” says Roxann Link, New England Region Junior Commissioner. “All of our clubs, players and coaches have enjoyed playing at the Connecticut Convention Center and are excited that we will be able to add more teams.”

“The New England Region is looking forward to the expansion of two weekends for our Winterfest tournament,” says Roxann Link, New England Region Junior Commissioner. “All of our clubs, players and coaches have enjoyed playing at the Connecticut Convention Center and are excited that we will be able to add more teams.”

Just over three years ago, NBC Sports launched a new state-of-the-art 300,000 square foot facility headquartered in Stamford, on a thirty-three acre campus (formerly the home of Clairol). The facility brought NBC Sports, NBC Sports Network, NBC Olympics, NBC Sports Digital, and NBC Regional Networks all under one roof. Connecticut’s First Five program, providing financial incentives to major business entities to relocate to the state, helped get the deal done. At the ribbon cutting for the facility in July 2013, just off exit 9 along I-95, NBC Sports Group Chairman Mark Lazarus said it was “built for every conceivable media platform, known today or yet to be built or conceived.”

Just over three years ago, NBC Sports launched a new state-of-the-art 300,000 square foot facility headquartered in Stamford, on a thirty-three acre campus (formerly the home of Clairol). The facility brought NBC Sports, NBC Sports Network, NBC Olympics, NBC Sports Digital, and NBC Regional Networks all under one roof. Connecticut’s First Five program, providing financial incentives to major business entities to relocate to the state, helped get the deal done. At the ribbon cutting for the facility in July 2013, just off exit 9 along I-95, NBC Sports Group Chairman Mark Lazarus said it was “built for every conceivable media platform, known today or yet to be built or conceived.”

iveness of social media. In addition, ratings from the Opening Ceremonies on NBC television were down substantially from the London Games. But that seems to have been the floor, not the ceiling, for viewership levels.

iveness of social media. In addition, ratings from the Opening Ceremonies on NBC television were down substantially from the London Games. But that seems to have been the floor, not the ceiling, for viewership levels.

The Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference

The Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference