Combatting Childhood Obesity Starts From Day One; Wide-Ranging Policies Proposed

/Less “screen time,” more physical activity, more nutritional foods and fewer sugary beverages – that’s the formula to prevent obesity from taking root in infants and toddlers in the formative years of childhood, according to new recommendations by the Child Health Development Institute (CHDI) of Connecticut. A series of “science-based policy opportunities” for Connecticut, outlined this week, also include support for breastfeeding in hospitals and child care centers. The need for stronger action is underscored by recent statistics. In Connecticut, one of every three kindergartners is overweight or obese, as is one of every three low-income children. Children who are overweight or obese are more likely, according to the policy brief, to have:

The need for stronger action is underscored by recent statistics. In Connecticut, one of every three kindergartners is overweight or obese, as is one of every three low-income children. Children who are overweight or obese are more likely, according to the policy brief, to have:

- risk factors for future heart disease, such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure

- a warning sign for type 2 diabetes called “abnormal glucose tolerance,” although many children are being diagnosed with the full-blown disease in increasing numbers

- breathing problems such as asthma

- gallstones, fatty liver disease, and gastroesophageal reflux (acid reflux and heartburn)

- problems with their joints

“Recent research shows that obesity may be very difficult to reverse if children are not at a healthy weight by 5 years of age,” the policy brief indicated. “Investing early in preventing childhood obesity yields benefits for all of us down the line by fostering healthier children, a healthier population overall and greatly reducing obesity-related health care costs over time.”

The policy brief recommends five ways Connecticut’s child care settings and hospitals can help our youngest children grow up at a healthy weight:

- Support breastfeeding in hospitals and in child care centers and group child care homes.

- Serve only healthy beverages in all child care settings.

- Help child care centers and group child care homes follow good nutrition guidelines.

- Increase physical activity time for infants and toddlers in all child care settings.

- Protect infants and toddlers in all child care settings from “screen time.”

The recommendations stress that “talking, playing, singing and interacting with people promotes brain development and encourages physical activity,” and urges that healthy infant and toddler development be encouraged by:

- Never placing them in front of televisions, computers, or tablets to occupy them

- Never allowing infants and toddlers to passively watch a television, computer, mobile phone or other screen that older children in the same room are watching

“Healthy lifelong weight begins at birth,” said Judith Meyers, President and CEO of CHDI and its parent organization the Children’s Fund of Connecticut. “Investing in obesity prevention policies makes sense for Connecticut.” Meyers added that “the numbers are staggering,” and it has become clear that “to really address this problem we need to prevent it in the first place.”

If Connecticut were to implement the five recommendations highlighted in the policy brief, it would be the first state in the nation to do so, officials said.  A number of the proposals have been successfully implemented in other jurisdictions, including states and cities. Marlene Schwartz, Director of UConn's Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, noted that Connecticut has long been a leader in providing nutritional lunches in schools, and said that now the state’s attention needs to move to the earlier years of childhood. “The field has realized that we need to start even earlier,” she said. Rudd also indicated that determining "policy changes that might help reduce the disparities" in Connecticut, which are apparent in race, ethnicity and socioeconomic data, is also essential.

A number of the proposals have been successfully implemented in other jurisdictions, including states and cities. Marlene Schwartz, Director of UConn's Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, noted that Connecticut has long been a leader in providing nutritional lunches in schools, and said that now the state’s attention needs to move to the earlier years of childhood. “The field has realized that we need to start even earlier,” she said. Rudd also indicated that determining "policy changes that might help reduce the disparities" in Connecticut, which are apparent in race, ethnicity and socioeconomic data, is also essential.

Legislation now pending at the State Capitol, which is not as comprehensive as the policy brief recommendations, is designed to "increase the physical health of children by prohibiting or limiting the serving of sweetened beverages in child care settings, prohibiting children's access to certain electronic devices in child care settings, and increasing children's participation in daily exercise." The proposed legislation, HB 5303, was recently approved by a 10-3 vote in the Committee on Children, but has an uncertain future before the full legislature.

Dealing with childhood obesity has been a challenge because of the “many different systems and programs that impact childhood development – which can also provide “many different places for opportunities to influence what happens.” Officials said that some of the policy proposals can be realized through legislative action, others by regulatory changes, and others through voluntary initiatives. They indicated that since Connecticut established the Office of Early Childhood in recent years, coordination of oversight and services has improved, which is an encouraging development. Child care settings provide an opportunity to impact a large proportion of the state’s pre-kindergarten children, but plans to disseminate the message more broadly, including through pediatrician’s offices, are being considered.

The recommendations call for “allowing toddlers 60-90 minutes during an 8-hour day for moderate to vigorous physical activity, including running, and “adherence to federal nutrition guidelines” including more whole grains and low-sugar cereals, no sugary drinks, and fewer fried foods and high-sodium foods. Through 11 months, infants should be served “no beverages other than breast milk or infant formula, and those 12 months through 2 years old should be served no beverages other than breast milk, unflavored full-fat milk water, and no more than 4 ounces of 100% fruit juice.”

The CHDI policy brief indicates that “childhood obesity can contribute to poor social and emotional health because overweight and obese children are often bullied and rejected by their peers as a result of their weight. That stress can affect every part of their development, interfering with their learning (cognitive), health (physical and mental), and social well-being.”

The recommendations, described as “affordable, achievable, common sense measures,” were prepared for CHDI as part of a grant to the UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, funded by the Children’s Fund of Connecticut. The author was public health policy consultant Roberta R. Friedman, ScM.

The recommendations, described as “affordable, achievable, common sense measures,” were prepared for CHDI as part of a grant to the UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, funded by the Children’s Fund of Connecticut. The author was public health policy consultant Roberta R. Friedman, ScM.

CHDI began focusing on strategies to promote healthy weight in children from birth to age two after publishing the IMPACT “Preventing Childhood Obesity: Maternal-Child Life Course Approach” in 2014. The report reviewed scientific research on the causes of obesity and explored implications for prevention and early intervention. In 2015, the Children’s Fund of Connecticut funded four obesity prevention projects in Connecticut that addressed health messaging, data development, policy development and baby-friendly hospitals.

IMPACT “Preventing Childhood Obesity: Maternal-Child Life Course Approach” in 2014. The report reviewed scientific research on the causes of obesity and explored implications for prevention and early intervention. In 2015, the Children’s Fund of Connecticut funded four obesity prevention projects in Connecticut that addressed health messaging, data development, policy development and baby-friendly hospitals.

In Connecticut, the social purpose sector employs between 14-17% of the workforce and generates $33.4 billion in revenues annually. Connecticut foundation giving supporting the sector totals more than $1 billion, but is primarily invested in the programs and outcomes of the sector giving very little attention to investment in leadership. In fact, nationally less than 1% of all foundation grants support leadership capacity and development. The social purpose sector is a vital, critical part of our state and yet is not often regarded as such in discussions of economic benefit, sustainability, leadership, innovation and job creation.

In Connecticut, the social purpose sector employs between 14-17% of the workforce and generates $33.4 billion in revenues annually. Connecticut foundation giving supporting the sector totals more than $1 billion, but is primarily invested in the programs and outcomes of the sector giving very little attention to investment in leadership. In fact, nationally less than 1% of all foundation grants support leadership capacity and development. The social purpose sector is a vital, critical part of our state and yet is not often regarded as such in discussions of economic benefit, sustainability, leadership, innovation and job creation.

At this point, there are a couple of things to note. First, while we have been talking about leadership transitions for many years, the recession delayed the major transition of leaders out of the sector until now. Second, there is no bench strength to call on from within these organizations when these leaders retire. Very little investment has been made to build the skills and capacity of middle managers to step up into leadership roles. Third, most of the departing leaders are Baby Boomers whose leadership roles were dependent on their willingness to work long hours in a professionalized volunteer sector. We will not fill these rolls with Millennials and Gen Xers for what we paid their predecessors.

At this point, there are a couple of things to note. First, while we have been talking about leadership transitions for many years, the recession delayed the major transition of leaders out of the sector until now. Second, there is no bench strength to call on from within these organizations when these leaders retire. Very little investment has been made to build the skills and capacity of middle managers to step up into leadership roles. Third, most of the departing leaders are Baby Boomers whose leadership roles were dependent on their willingness to work long hours in a professionalized volunteer sector. We will not fill these rolls with Millennials and Gen Xers for what we paid their predecessors.

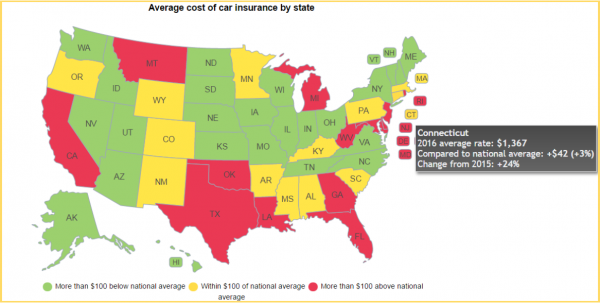

The national average for a full-coverage policy as featured in the Insure.com report came in at $1,325 this year – a slight increase from last year’s average of $1,311. Rates varied from a low of $808 a year in Maine to a budget-busting $2,738 in Michigan. Insurance rates in Michigan are more than double (107 percent) the national average.

The national average for a full-coverage policy as featured in the Insure.com report came in at $1,325 this year – a slight increase from last year’s average of $1,311. Rates varied from a low of $808 a year in Maine to a budget-busting $2,738 in Michigan. Insurance rates in Michigan are more than double (107 percent) the national average.